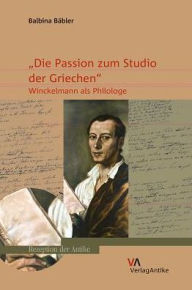

'Die Passion zum Studio der Griechen': Winckelmann als Philologe

by Balbina Babler

2020-05-07 04:08:31

'Die Passion zum Studio der Griechen': Winckelmann als Philologe

by Balbina Babler

2020-05-07 04:08:31

English summary:Many statements of Winckelmann - in his personal letters as well as in the prefaces of his main works - show that he considered himself to be as much a classical philologist as anything else. All of his main works contain a compre...

Read more

English summary:Many statements of Winckelmann - in his personal letters as well as in the prefaces of his main works - show that he considered himself to be as much a classical philologist as anything else. All of his main works contain a comprehensive register of ancient authors explained and emended throughout the book. He claimed that his own method of explanations and emendations of text passages via the interpretation of a related work of ancient art was superior to orthodox textual criticism and textual comparison of manuscripts. Yet Winckelmann's philological ambitions, although so important for himself, have never been the subject of a study. This book focuses therefore on an important aspect of Winckelmann's work that has been almost entirely neglected so far in scholarship. A decisive role in this research is played by the scholar's Nachlass that encompasses many thousands of handwritten pages to be found today mainly in the libraries of Paris, Hamburg and Savignano. They contain not only extensive excerpts of ancient authors, but also notes and records from libraries as well as preliminary studies in view of planned editions and scholarly work of textual criticism. The potential of this source is still not fully exploited. The subject of Winckelmann as a philologist shall be approached from different angles: An introductory part (1.1.) gives an overview of older and new research dedicated to the parts of Winckelmann's work concerning ancient authors. The second part (1.2.) opens up a new possibility of access to Winckelmann's life and work through a close examination of his autobiography, which consists of 67 quotations taken almost entirely from Greek (and some Latin) authors. So far, the only scholarship done on these important documents is an article by Schadewaldt of 1970 that is not entirely satisfying. Part 2 focuses on Winckelmann's education within the context of the contemporary situation of Classical Philology in Germany. Here the main questions (chapters 2.1. and 2.2.) are: Which ancient authors did he get to know in his youth? What kind of philological skills and knowledge could the schools and universities he attended provide him with? And what were the possibilities of a solid philological education on the whole in these times? Biographical aspects will be considered in this context only if they contribute to answering these questions. Chapter 2.3. attempts to give an insight into Winckelmann's stint as a schoolteacher in the little town of Seehausen (1743-1748). During this time he composed ten Latin poems that are here for the first time edited, translated and commented. It is telling that Winckelmann resorted to ancient models and examples to express his feelings at a time in his life when he was deeply unhappy. Part 3 is dedicated to Winckelmann's strictly philological work, which was done partly still in Germany, but for the greater part in Rome. In chap. 3.1. the fragmentary attempt at a commentary on Aristophanes' Lysistrata is edited, translated and commented; chap. 3.2. analyses his essay on Xenophon. Chap. 3.3. deals with his preliminary studies for various philological treatises, especially his extensive notes and records of editions and manuscripts in Roman libraries (3.3.3.), and the catalogues of words and expressions on Aeschylus and the Greek codices in the Biblioteca Vaticana he started to compile (3.3.4.). Chap. 3.4. looks at the editions of ancient authors he planned to publish; this was a recurrent subject from the beginning of his stay in Rome 1755 until the end of his life. Although no edition was ever completed and published, the choice of authors (e. g. scholia on Plato, fragments of comic and tragic authors, Libanius, Catullus with illustrations) shows that he had a good notion of promising subjects: for example, authors that lacked an edition. Part 4 deals with the results of those extensive preliminary studies that found their way into his main works. Some examples of his conjectures and interpretations of passages of ancient texts are examined, as well as an example of his discussion of conjectures of contemporaneous scholars. It can be shown that Winckelmann did not entirely live up to his own aim alte Scribenten .... zu verbessern (to emend ... the ancient authors) with the help of ancient works of art. He mainly used traditional philological methods and arguments based on other passages of texts. His interpretations and conjectures were often too fanciful, especially when he tried to save the text of an ancient author at all costs. However, when he did summon an ancient monument to explain or emend a passage in a Greek or Latin author, the result is often convincing. Winckelmann's philological work can therefore not be summarily dismissed; rather, every one of his arguments should be checked individually. The last part (5) is dedicated to the exhaustive discussions and critical reviews of Winckelmann's works by Christian Gottlob Heyne,

Less