- Browse Category

Subjects

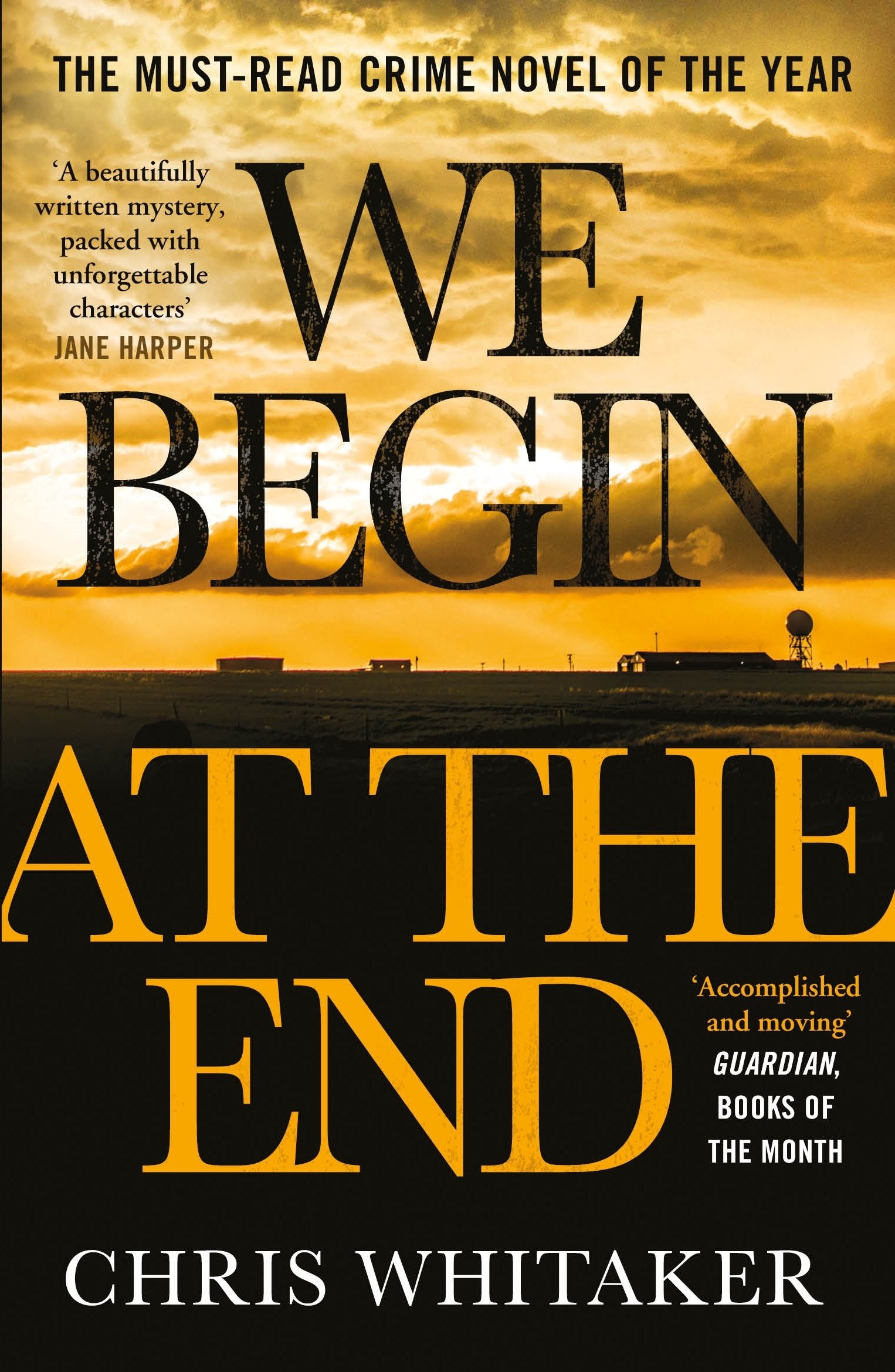

We Begin at the EndLearn More

We Begin at the EndLearn More - Choice Picks

- Top 100 Free Books

- Blog

- Recently Added

- Submit your eBook

password reset instructions

As a blind person might see the world if the gift of sight were suddenly returned—this is how we might describe the effect of William Turner''s paintings on the observer. John Ruskin, Turner''s uncompromising 19th-century defender, alluded to this idea when he spoke of an "innocence of the eye" which perceived the world''s colours and forms before it could recognize their significance.

But to develop such a style, William Turner (1775-1851) first had to overcome the legacy of late rococo academic teachings. He was simultaneously a romantic and a realist—and yet he transcended both styles. His landscapes, far in advance of their time, have been called forerunners of Impressionism, yet they also possess traits that influenced Expressionism, and many of his late compositions are undeniably surrealistic.

Turner''s art cannot be bound by such classifications, and remains an oddity to art history even today. His work arises from a unique relation to the nature that it depicts: through his brilliant sketches, he found a rigorously open kind of painting in which nature sets free the use of colour. And through the workings of the natural elements—especially atmospheric light—Turner confronted nature at the point where nature itself is an image. This book opens up Turner''s paintings for the eye, demonstrating that he was not simply illustrating nature, but that his pictures speak directly to the eye as nature does itself—through a world of light and colour.

- File size

- Print pages

- Publisher

- Publication date

- Language

- ISBN

- 10.4x8.5x0.5inches

- 96

- Taschen

- September 1, 2015

- English

- 9783836504546

.jpg)

.EBOOK COVER.jpg)

.jpg)